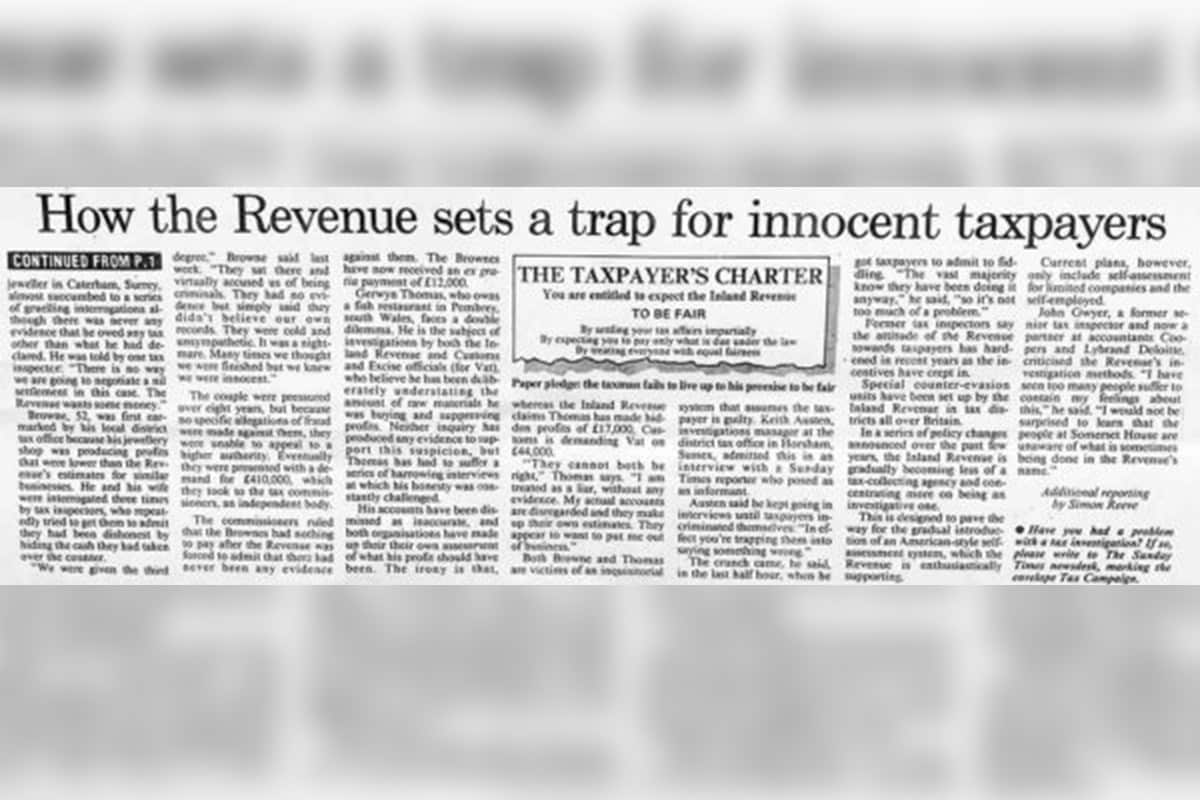

How the Revenue Sets a Trap for Innocent Taxpayers

By Peter Hounam – additional reporting by Simon Reeve

Sunday Times, April 19, 1992

CONTINUED FROM P. 1

…jeweller in Caterham, Surrey, almost succumbed to a series of gruelling interrogations although there was never any evidence that he owed any tax other than what he had declared. He was told by one tax inspector: “There is no way we are going to negotiate a nil settlement in this case. The Revenue wants some money.”

Browne, 52, was first earmarked by his local district tax office because his jewellery shop was producing profits that were lower than the Revenue’s estimates for similar businesses. He and his wife were interrogated three times edly tried to get them to admit they had been dishonest by hiding the cash they had taken over the counter.

“We were given the third degree,” Browne said last week. “They sat there and virtually accused us of being criminals. They had no evidence but simply said they didn’t believe our own records. They were cold and unsympathetic. It was a nightmare. Many times we thought we were finished but we knew we were innocent.”

The couple were pressured over eight years, but because no specific allegations of fraud were made against them, they were unable to appeal to a higher authority. Eventually they were presented with a demand for £410,000, which they took to the tax commissioners, an independent body. The commissioners ruled that the Brownes had nothing forced to admit that there had never been any evidence against them. The Brownes have now received an ex gratia payment of £12,000.

Gerwyn Thomas, who owns a fish restaurant in Pembrey, south Wales, faces a double dilemma. He is the subject of investigations by both the Inland Revenue and Customs and Excise officials (for Vat), who believe he has been deliberately understating the amount of raw materials he was buying and suppressing profits. Neither inquiry has produced any evidence to support this suspicion, but Thomas has had to suffer a series of harrowing interviews at which his honesty was constantly challenged.

His accounts have been dismissed as inaccurate, and both organisations have made or what his profit should have been. The irony is that, whereas the Inland Revenue claims Thomas has made hidden profits of £17,000, Customs is demanding Vat on £44,000.

“They cannot both be right,” Thomas says. “I am treated as a liar, without any evidence. My actual accounts are disregarded and they make up their own estimates. They appear to want to put me out of business.”

Both Browne and Thomas are victims of an inquisitorial system that assumes the taxpayer is guilty. Keith Austen, investigations manager at the district tax office in Horsham, Sussex, admitted this in an interview with a Sunday Times reporter who posed as an informant.

Austen said he kept going in interviews until taxpayers incriminated themselves. “In effect you’re trapping them into saying something wrong.”

The crunch came, he said in the last half hour, when he got taxpayers to admit to fiddling. “The vast majority know they have been doing it anyway,” he said, “so it’s not too much of a problem.”

Former tax inspectors say the attitude of the Revenue towards taxpayers has hardened in recent years as the incentives have crept in.

Special counter-evasion units have been set up by the Inland Revenue in tax districts all over Britain.

In a series of policy changes announced over the past few years, the Inland Revenue is gradually becoming less of a tax-collecting agency and con-centrating more on being an investigative one.

This is designed to pave the way for the gradual introduction of an American-style self-assessment system, which the Revenue is enthusiastically supporting.

Current plans, however, only include self-assessment for limited companies and the self employed.

John Gwyer, a former senior tax inspector and now a partner at accountants Coopers and Lybrand Deloitte, criticised the Revenue’s investigation methods.”I have seen too many people suffer to contain my feelings about this,” he said. “I would not be surprised to learn that the people at Somerset House are unaware of what is sometimes being done in the Revenue’s name.”