How I Escaped Mossad’s Clutches

Daily Telegraph, February 20, 2010

IF Mossad was behind the murder of Hamas military commander Mahmoud al-Mabhouh in a Dubai hotel last month it should shock nobody given their organisation’s violent history.

In the 1980s, when working for The Sunday Times, I tracked down an Israeli technician called Mordechai Vanunu in Australia who went on to reveal the innermost secrets of Israel’s top-secret nuclear weapons centre at Dimona in the Negev Desert. He had worked there and had been able to smuggle out photographs of the plutonium separation plant and bomb making machinery.

I debriefed him at length in Sydney and then brought him to London to be cross-questioned by experts. Vanunu was aware that he could be a Mossad target and for this reason he accepted tight security precautions, but he later grew impatient.

Strolling alone around Leicester Square, London, he met into an attractive blond American tourist called Cindy. They had a coffee, and arranged to go to the cinema. Vanunu had stupidly walked into a classic Mossad honey trap.

He said nothing to me of his dangerous liaison until it was too late. After hearing about Cindy one Monday morning, I pointedly warned him she might be an Israel agent but he dismissed the notion. I suggested meeting him and Cindy for dinner that evening but he cancelled and then disappeared. It was several weeks before Israel announced they were holding him.

Mordechai Vanunu’s motive had been to expose his country’s clandestine WMD programme so international pressure would end it. Tragically, he was now incarcerated in a Tel Aviv cell facing charges of treason and espionage for which he received a sentence of 18 years, the first eleven of which were endured in solitary confinement.

Mossad failed in its object of stopping Vanunu’s story being published – we went to print the same week he vanished – but our star witness was missing and I now concentrated on exposing who was responsible. We suspected it must have been the famed Mossad. I remembered seeing two people in a car watching my house early one morning and now realised it was a big operation. But who was the mysterious Cindy?

It took nearly a year to track her down, expose her identity and, to my great satisfaction, ruin her career in espionage. We succeeded because Mossad had taken too many shortcuts, and it was Vanunu himself who gave us the crucial clue.

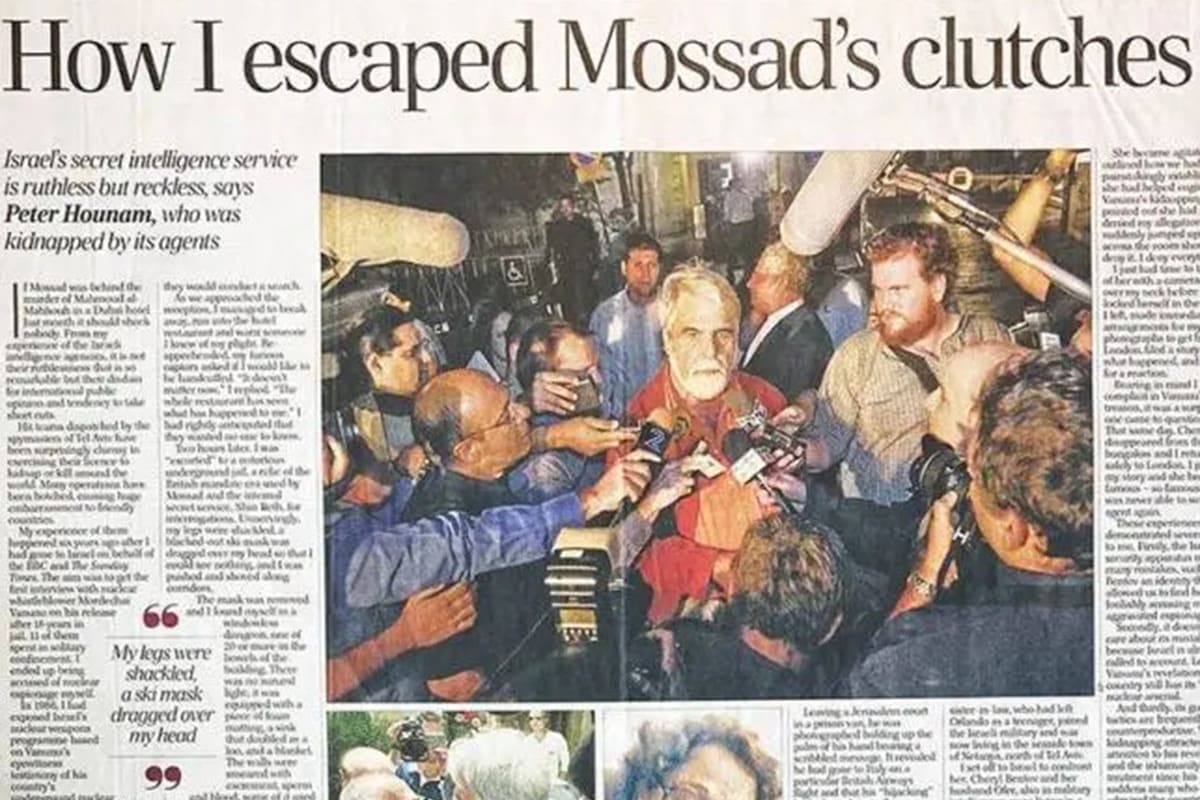

Leaving a Jerusalem court in a prison van one day, as photographers stood by, he famously pressed the palm of his hand, bearing a scribbled message, up to the window. It revealed he had gone to Italy on a particular British Airways flight and that his ‘hijacking’ had taken place in Rome.

Boarding passes showed he had flown with a Cindy Hanin, and the most likely Cindy Hanin we eventually found lived in Orlando, Florida. She was due to get married and was clearly not a direct suspect but she was Jewish and I had a hunch the real spy might have a family connection.

The trail led to Cheryl Bentov, her future sister-in-law who had left Orlando as a teenager, joined the Israeli military and was now living in the seaside town of Netanya, north of Tel Aviv. Evidence from London hotels used by Cindy confirmed my suspicions, and I set off to Israel to confront her.

It was soon evident working for Mossad is not a pathway to riches. Cheryl Bentov and her husband Ofer,’ also in military intelligence, were living in a rundown bungalow in a street beside the main Haifa highway, but it was handy for the new Mossad headquarters on West Glilot junction just a few miles to the south.

At her door I announced I was from The Sunday Times and asked if I could have a word. There was a flash of shocked recognition in Bentov’s eyes. “Er yes. Come on in,” she replied cautiously, and led the way.

I outlined how we had painstakingly established she was the spy who had played a key role in engineering Vanunu’s kidnapping. Agitated, she complained I was tape recording her, and when I pointed out she had not denied my allegations she suddenly jumped up and ran across the room shouting, “I deny it. I deny everything.”

I just had time to take a shot of her with a camera slung over my neck before she locked herself in the bedroom, refusing all attempts to persuade her to come out. I then left, made immediate arrangements for my photographs to get back to London, filed a story about what happened, and stood by for a reaction.

I had been to Israel several times reporting on Vanunu with no problems, although it was clear I was being watched. Bearing in mind I had been complicit in Vanunu’s alleged treason, this was something of a surprise, but my confrontation with Cheryl Bentov led to no knocks at the door. She disappeared from the bungalow in Netanya and I returned safely to London. I published my story and she became famous, so famous that she was never able to act as an agent again.

Years later the biggest Israeli newspaper, Yediot Ahronot quoted a close friend of Cheryl’s in Florida where she had returned: “She left Israel to flee the media and the people who burrowed into her life. This bothered her a lot.

“She was terrified about journalists who came into her home and asked her questions. She felt a need to run. Since this affair Cheryl wants only one thing: a normal, quiet life.” Eighteen months ago her picture pops up on the web, smiling alongside husband Ofer on a walking holiday in Slovakia.

It was another 17 years – in 2004, before I encountered any real problems, probably because I had pushed my luck too many times. In Israel public hatred of Vanunu was so great the authorities had made him serve his full sentence. On his release in April 2004, my task was to get the first TV and newspaper interview but just beforehand he was prohibited from talking to foreigners or leaving the country.

We got around it by using an Israeli journalist to speak to him, with me sitting in the background. One version of the film was impounded that night but a second copy got to London. It was while driving though Tel Aviv one afternoon afterwards that my luck ran out.

A car suddenly pulled into my path, others stopped beside and behind me, and I was dragged out. A man with a police cap said I was under arrest and that I was going to Jerusalem for questioning. But first we would visit my hotel room where they would conduct a search.

Fortunately, on the way towards reception I managed to break away and warn someone I knew in a nearby restaurant of my plight. Re-apprehended, they carried out the search and I ended up in a notorious underground jail used by Mossad and the internal secret service Shin Beth for interrogations.

Unnervingly, I was shackled and had a blacked-out ski mask pushed over my head and I was guided periodically from a windowless, excrement-soiled dungeon, to their brightly lit interrogation room. It eventually became clear as they tried to grill me that they thought I had hidden some extra film footage revealing more of Vanunu’s secrets. The stupidity of this was that Vanunu had no more nuclear secrets.

They attempted to keep me locked up for four days but international pressure and the intense interest of the Israeli media forced them to let me out, shaken but unharmed, after 24 hours.

These experiences have demonstrated several things to me. Firstly the Israeli security apparatus makes many mistakes such as giving Bentov an identity that allowed us to find her, or foolishly accusing me of aggravated espionage.

Secondly, they don’t much care about their mistakes because Israel is almost never called to account. Even after Vanunu’s revelations, the country has had little trouble in keeping and building up its nuclear arsenal.

And thirdly, its gung-ho tactics are frequently counterproductive. It was Vanunu’s kidnapping that mostly attracted attention to his revelations, and it is the inhumanity of his treatment since his release that leads many to view Israel as a country that has lost it way since its foundation.

Surprisingly perhaps, I like Israel and have many friends there including Mordechai Vanunu. Alas I cannot return. I was banned after my last run in – on orders of Mossad.