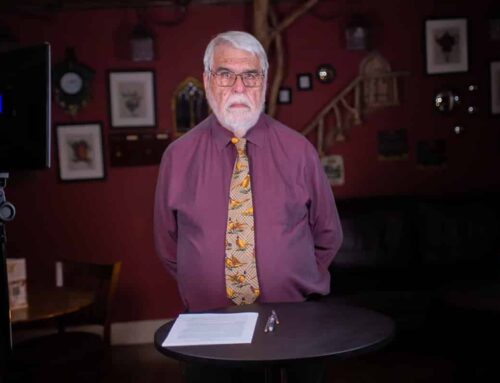

Investigative Journalism

Investigative journalism is a high-risk business because it means engaging with unscrupulous people and revealing nasty human traits. It is about corruption, cheating, conspiracy, cruelty and cover-ups. My favourite word sums it up: skulduggery.

While delving into this wilderness of nastiness for decades I have seen the worst of human failings at first hand. Uncovering what others want buried can be a provocative act. Finding out means asking difficult questions and entering challenging environments here and abroad. Now and again you meet dodgy and dangerous people.

Exposing human fallibility

Inevitably it means upsetting – and unsettling ruthless characters who thought their dark secrets were safely obscured. It is fascinating of course but unlike the police, we have no right to pry. Our special power is that of public exposure – with the hope that now and again wrongs will be righted.

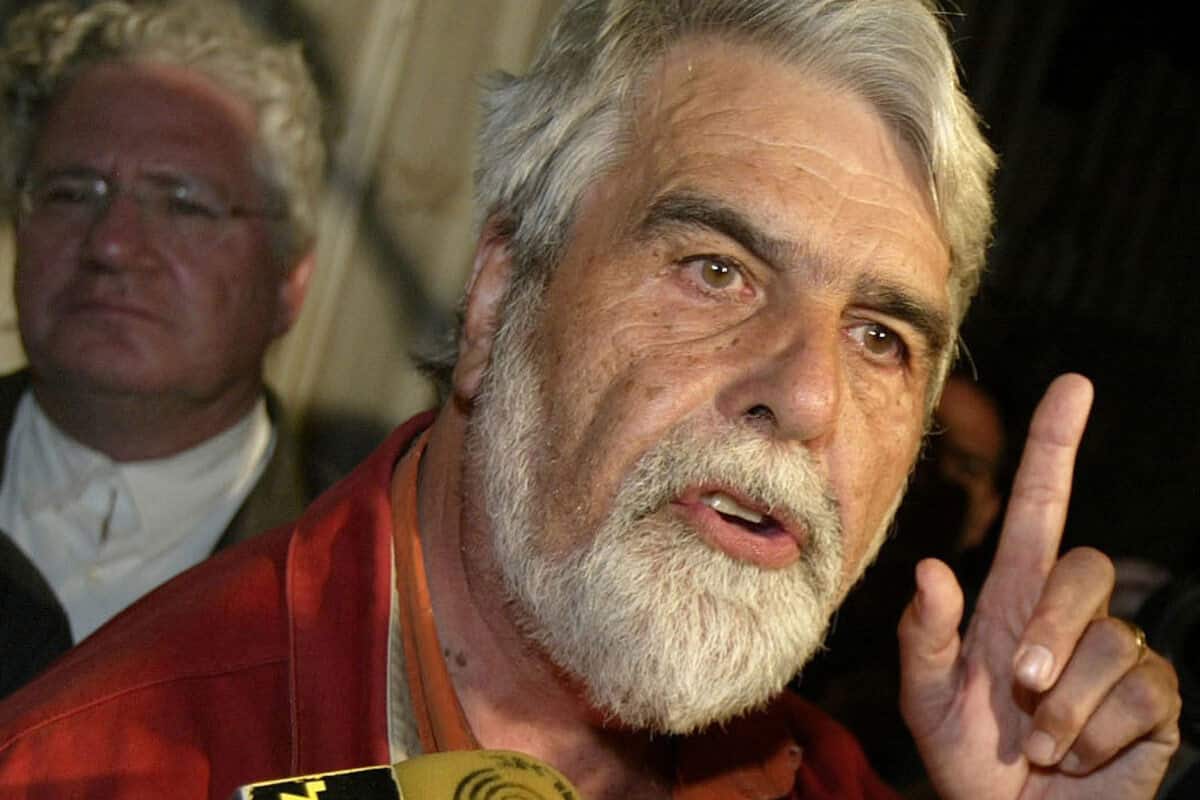

Being intrusive is part of the game but I have never had to put my foot physically in a door to prevent it being slammed in my face. Perhaps it helps I have, seemingly, a forceful personality and a hefty presence. What I think crucial is of skill in dealing with people of all sorts and building their trust.

You have to be thick-skinned but also sensitive to what might unlock someone’s natural inclination to shut you out, to know what buttons to push. Up-front, when you are face to face with your informant, there is just a brief opportunity – a minute or two – to foster a dialogue or leave empty-handed.

You have to be incessantly curious, an urge to discover why something seems out of kilter. All around us there are interesting stories, big and small – like my story about the bird-shooting vicar in our BackFlash column. In essence we need a strong emotional instinct signalling what is right and what is wrong. Not, I must stress, what is illegal or illegal. Alas, immorality is a much wider human failings; fortunately, civilisation is governed by higher standards than the criminal law.

Exposing human fallibility whether institutional or social is sometimes risky. The best protection from reprisals by people we have been called to account is to get the story into print or onto the air.

“O, what a tangled web we weave when first we practise to deceive!”

That sage advice by Sir Walter Scott was never more appropriate.

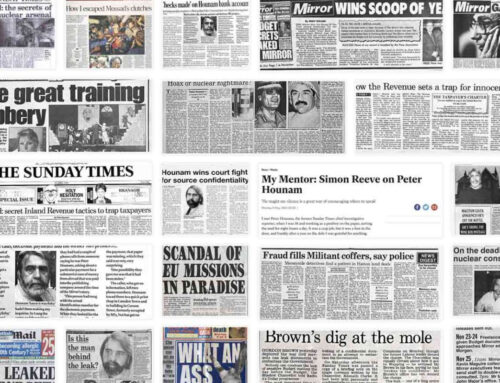

It is a sad thing that only a tiny portion of the press and broadcasting community have the urge or resources to probe into wrong-doing, injustice and the new scourge of disinformation. This is even more true now, while I am delving into a miasma of skulduggery in the Middle East, than when my first modest scoop appeared in a local paper in 1972 – see BackFlash.

Cost is a factor but, ultimately, it is not an excuse. The media has a duty to expose and provide the means to do it. It makes our societies better which is why Napoleon said: “I fear three newspapers more than a hundred thousand bayonets.” And it makes good business sense, because good investigative journalism builds circulations and boosts ratings.

Hi can u get back to me ref: DIRTY DES former morriston quarry boss Max Recovery Holdings Ltd swansea you covered him in October 1993